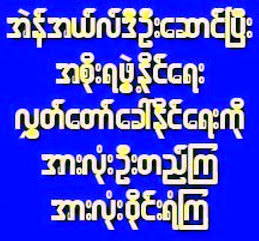

Volunteers from a Rangoon-based social welfare association, Free Funeral Service Society, cremate decayed bodies in Kungyangon Township of Rangoon Division. (Photo: AFP)

Volunteers from a Rangoon-based social welfare association, Free Funeral Service Society, cremate decayed bodies in Kungyangon Township of Rangoon Division. (Photo: AFP)Thousands of people killed in last month's devastating cyclone in Burma may never be formally identified, due to the slow place of body recovery since the tragedy, say aid workers.

The scale of the disaster—and its wide geographical spread—has meant survivors in many remote communities of the Irrawaddy Delta were left to deal with a large number of bodies, of both family members and strangers, with little, if any, official support.

It is clear from the information we have been given that there is no planned, concerted or consistent approach being taken," Craig Strathern, a spokesman for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), told IRIN from Rangoon.

"Mostly it's local communities dealing with the immediate problem in their vicinity," he said.

Some cyclone survivors told aid workers of disposing of bodies any way they could—through burial, cremation, or other methods—in the quest to restore normalcy and get on with rebuilding their lives.

"Farmers were saying they just put some bodies in the river," said John Sparrow, a spokesman for the International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC), who has just returned from the disaster area. "They were desperate to start their paddy season. If they found bodies they couldn't recognize, they just threw them into the river."

Cyclone Nargis, and the accompanying tidal surge that swept up to 35kms inward, left an estimated 133,000 people dead or missing on 2 and 3 May and 2.4 million destitute.

But more than six weeks on, as aid agencies struggle to distribute food, water and other essential supplies, disposing of bodies has been considered far less of a priority, especially as the World Health Organization (WHO) has said the corpses posed little health risk.

Disposal efforts

In some of the more populated areas and key towns, local authorities did make concerted efforts to collect and dispose of bodies, while extra manpower was also brought in from Rangoon to help with the task.

However, villagers in more remote or isolated areas were left to do it alone.

Reports indicate that in many waterways and remote areas without many survivors, bodies have yet to be collected, and recently more than 300 bodies were said to have washed up on a popular beach in Mon state, hundreds of kilometers from the cyclone's point of impact.

"It's been very much left to the local township commanders and leaders to decide how to deal with the problem," Sparrow said. "You are talking about a widely dispersed area, with limited transport and logistics. It's not surprising those have been prioritized for relief and emergency distribution."

Tsunami precedent

The slow pace of body disposal and lack of any large-scale victim identification effort are in stark contrast with the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami, which killed more than 200,000 people.

In Thailand—where foreigners, mainly European tourists, accounted for half the estimated 8,345 dead—authorities set up a forensic operation to identify victims, an initiative supported financially and technically by governments around the world.

The Thai operation used forensic evidence, including fingerprinting, dental records and DNA matching, to try to identify bodies.

In Indonesia, where more than 165,000 people died, efforts were more rudimentary, including visual identification in the first few days, or by personal effects and SIM cards.

But there was a big, official drive to bury bodies quickly in accordance with Islamic custom, and to create marked graves as memorial sites.

"In Indonesia, people accepted they may never find their loved ones, but at least they could go to a marked memorial even if they weren't 100 percent sure their relatives were there," Strathern said.

Identification issues

Burma's cyclone survivors appear resigned to accepting lost loved ones without definite proof, or any ceremonial resting places, while local laws mean formal verification of death is not required.

"Here there is the assumption that if we haven't seen our loved ones for two or three weeks they are probably dead," Strathern said.

No comments:

Post a Comment