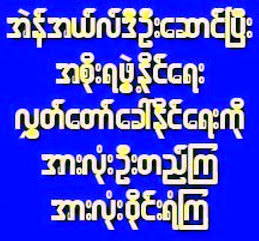

Refugee children eat donated food in Kyauktan Township, 20 miles south of Rangoon. (Photo: AFP)

There may be a global food crisis, but few countries are feeling the pinch like Burma. And for thousands of people in the Irrawaddy delta, desperate times lie ahead

MA Thein is a senior clerk at the Ministry of Industry in Rangoon. Her husband sells medical supplies, and her son works in a noodle factory. They all work full-time. Despite the family’s combined earnings of 140,000 kyat (US $117) per month, she still can’t afford to put one balanced meal on the table each day.In June, the United Nations met in Rome to discuss the global food crisis. Prices of staple foods were going through the roof and food riots had broken out across the world, from Egypt to Indonesia to Peru.But Ma Thein didn’t have to watch the news on TV to know there was a food crisis, nor did anyone else in Burma. The unstable economy, international sanctions, corruption, bird flu epidemics and a poor annual rice harvest had already pushed food prices higher this year.Then, on May 2-3, Cyclone Nargis ravaged the Irrawaddy delta, the source of 90 percent of Burma’s rice and the majority of its agricultural produce. Overnight, 2.5 million acres (more than 1 million hectares) of rice paddies were inundated with seawater and an estimated 150,000 livestock were killed. The Irrawaddy delta—the so-called “rice bowl” of Burma—was devastated.The following day, Ma Thein joined the throngs of other panicking customers at the central market. Tempers flared as some influential people pulled up in a truck and bought up as many sacks of rice as the truck could hold. Overnight, prices had almost doubled. No matter how she budgeted, Ma Thein simply could not afford to buy provisions for the month. Beef had risen from 3,000 kyat ($2.50) to 5,000 kyat ($4.17) per viss (1.63 kilograms). The cost of pork had increased 33 percent and the price of chicken had gone from 5,000 kyat to 7,000 kyat ($5.83) per viss. That night, Ma Thein’s husband suggested they buy fish. Fish was also more expensive, but market traders were prepared to make deals, because many people were reluctant to eat fish and seafood for fear the fish had been feeding on bodies in the waterways of the delta. Ma Thein’s husband and son went fishing at a lake that weekend. Many farmers in the delta—who were, until recently, relatively self-sufficient—are now without animals or crops and must buy their food at the market. The military junta, for its part, sanctimoniously suggested that survivors in the delta hunt frogs as a source of protein. At a local market in the delta, an elderly woman cried when she realized she had no more money to buy food this month. She pointed to her shopping basket—a small bundle of chin paung (sour roselle leaves), a bunch of water spinach, two eggs, some frog meat and a viss of salt.The cyclone also damaged salt farms in Irrawaddy and Rangoon divisions and in Mon State, causing a salt shortage and driving prices up. State-run media reported that a total of 24,431 acres (9,890 hectares) of state-owned and private salt farms were affected by Nargis. Before the cyclone struck, one viss of salt was selling wholesale for 450 kyat (38 cents). The same amount by the end of June cost 1,200 kyat ($1) with retail prices as high as 1,500 kyat ($1.25) per viss. A salt merchant in Rangoon said it was clear production had decreased severely and that prices would never return to previous levels. The most important food source of all—rice, which is the foundation of almost every Burmese meal—doubled in price. High-quality rice, such as paw sun, was selling for 28,500 kyat ($23.75) per 50-kilogram sack before the cyclone. Shortly after the disaster the price of a sack rose to 50,000 kyat ($41.67) before leveling off at around 45,000 kyat ($37.50) at most markets. The price of a sack of ziyar (low-quality rice) rose to 28,000 kyat ($23.33) in the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis before leveling off at 20,000 kyat per sack. “People have been forced to lower their food standards in order to make end meets,” said a rice trader at the Bayintnaung wholesale market. “For instance, some well-off customers have had to change from high-quality paw sun rice to a lower quality, such as paw kywe.

Those who used to eat paw kywe are now buying ziyar.”According to the Rangoon rice trader, truckloads of rice that was spoilt by seawater began arriving in the city after the cyclone. The rice was soon in high demand among the poorer people of the city. A Rangoon physician said he could not foresee any harm from eating seawater-soaked rice, although its nutritional value is very low. For many people there is no alternative. According to the rice trader, the amount of rice arriving in Rangoon by mid-June had significantly decreased. Prior to the cyclone, 60,000 to 80,000 sacks of rice—mostly from the Irrawaddy delta—were transported to Rangoon markets every day. Now traders and merchants are struggling to bring in 40,000 sacks a day, a minimum requirement for the Rangoon market.According to official figures, in 2007, Burma produced 30 million metric tons of rice, of which 18.9 million tons were exported. The 55 million inhabitants of Burma require 17 million tons of rice per year—each person consuming an average of 234 kilograms annually. Although the military government has claimed it is trying to restore rice production in the disaster-affected areas, independent experts estimate that only 20 percent of rice paddies will be reclaimed in time for this year’s harvest. In the meantime, rice traders say prices will continue rising. Even before the natural disaster, the diet of many poor people in Burma consisted of low-quality rice and little more. A bowl of rice is usually accompanied by sour roselle leaf soup, a spoonful of ngapi (fish paste) and a handful of leaves, roots and green vegetables. Many people frequently go without any kind of meat and the diet is as unchanging as it is unappetizing. Saw Klo Htoo, a Christian Karen who is destitute after losing everything in the cyclone, is unable to afford even ziyar rice and has turned to the only remaining option—rice that was soaked in seawater during the cyclone. This rice, which would usually be considered ruined and tossed away, is now being bought up readily by those who cannot afford anything else. Saw Klo Htoo’s wife, Rebecca, was able to purchase a sack at the local market for 13,000 kyat ($10.83), almost half the price of ziyar rice.“When I opened the sack I could immediately smell it was moldy,” said Rebecca. “The rice grains were broken and colored yellow. I laid the rice out on the ground to try to dry it out. But when I cooked the rice, the grains quickly softened and stuck together.”Rebecca said that when she served the rice it had the consistency of a thick soup. It tasted awful and gave her young daughter a stomachache. Saw Klo Htoo said that even though his family is depressed, he can see that the other families around him are in a similar situation—they are also eating the yellow, foul-smelling rice.“I have never eaten moldy rice before,” he said. “But when I asked the neighbors, they said it was fine and that they had been eating it for two weeks. With all the prices increasing, it is all we can afford.”

No comments:

Post a Comment