Most countries provide some form of absentee voting for nationals who live abroad or facilitate voting for internal migrants who have returned home to vote.

Migrants represent a constituency that can be a powerful lobby in referendums and elections, and can, sometimes, determine an election’s outcome.

In Zimbabwe, The Congress of Trade Unions has called on 3 million Zimbabweans living and working in South Africa to return home to vote in the March 29th election.

In a recent election in Kelantan, Malaysia, the Barisan Nasional Party blamed its defeat on the failure of a large number of Kelantanese living outside the state to return home to vote.

In Thailand, Section 99 of the 2007 Constitution enshrines the right of Thai nationals who reside outside their constituency or outside the country to vote. In the December national election, polling booths for absentee voters were set up a week before the vote. For Thai migrants, who returned home to vote, a public holiday was declared to allow more time to travel.

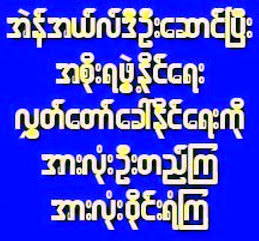

In Burma, with a referendum on the constitution scheduled in May, Burmese migrants are wondering will they be able to exercise their right to vote?

Burmese migrants have never had the opportunity to vote, although many have grown up hearing stories from their parents about voting in the 1990 election, only to have the vote ignored by the junta.

While migrants fear the same thing may happen this time, they will never know unless they are able to vote.

There are many hurdles for Burmese migrants to overcome, if they are to be allowed to vote. The deck, as usual, seems stacked against them.

The first hurdle entails knowing how to register to vote. Embassies are usually the best source of information for overseas nationals on such issues, but it is no easy task to get any information from the Burmese embassy in Bangkok.

Families in Burma are being instructed to tell their migrant relatives to return home quickly to be included on the voting registrar and obtain an ID card to be eligible to vote.

If successful, that could entail making two trips home: one to register and one to cast a “No” or “Yes” vote. Such trips would not only cost migrants precious money and time, but could also cost them their legal status in Thailand.

When migrant workers in Thailand register for a temporary work permit they are legally confined to the province where they register. Crossing a provincial border could lead to the loss of their legal status and crossing the border into Burma would automatically render the migrant illegal under current laws.

Some 367,834 Burmese migrants in Thailand hold a work permit that will expire on June 30th. Registration to extend the permit for another year begins on June 1. If these migrants choose to return home to vote, would they be able to return to Thailand to register for a work permit again?

Even if the Thai government decided to support the migrants’ right to vote and facilitated their return, migrants would have another hurdle to overcome: their employers.

Employers of migrant workers are usually reluctant to give migrants time off from work; would they support a week off to return home to vote? Would their jobs be there when they returned?

According to a recent article in The Bangkok Post, Thai Foreign Minister Noppadon Pattama said: “If Myanmar [Burma] wants assistance from Thailand (on the referendum), we are ready to offer help as a friendly country.” Thailand’s help is badly needed by the 360,000 registered Burmese migrants and 1.2 million unregistered migrants.

If the Burmese embassy in Bangkok becomes a polling station, Thailand’s help would be needed to issue migrants temporary travel passes to go to Bangkok to vote.

The Burmese regime could also set up polling stations located close to the Thai border specifically for migrants as they do on the American-Mexican border. In this scenario Thailand would need to provide some sort of document or amnesty on travel restrictions to allow migrants to travel safely to and from the border.

If the regime demands that migrants return home first to register and then to vote, Thailand’s assistance would be needed to provide travel documents or border passes and to ensure that employers grant workers time off to perform their civil duty and guarantee their jobs upon their return.

The Burmese regime has provided almost no information about the referendum process, the actual voting or the contents of the constitution.

If Thailand is open hearted and willing to aid Burmese migrants who want to vote in the referendum, it will be necessary to act quickly. And if Asean is truly a caring community, it will actively support systems for Burmese migrants in Malaysia and Singapore to also be able to vote.

3.23.2008

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)